Chris Sheppard (Waseda, Japan)

Abstract

(English)

In order for an

English for Specific Purposes (ESP) language program to be

successful, an evidence-based approach to its curriculum design is

essential. Nation and Macalister’s (2010) curriculum design model

requires a careful consideration of learner’s needs and situation

as well as implementation of language learning principles. In this

paper, a description of a curriculum design process is provided,

then, the choices made while designing a curriculum for a large scale

ESP program are discussed with reference to this curriculum design

process.

Keywords:

ESP, curriculum design, skill based learning, complexity

Abstract

(Deutsch)

Damit ein

fachbezogenes Fremdsprachenprogramm in Englisch (ESP-Programm)

erfolgreich etabliert werden kann, ist ein evidenzbasiertes

Herangehen an das Curriculum-Design zwingend erforderlich. Das Modell

von Nation & Macalister (2010) fordert eine sorgfältige Analyse

der Lernerbedürfnisse, der Lernsituation sowie der Umsetzung der

Sprachlernprinzipien. In dem vorliegenden Beitrag wird der

Curriculum-Entwicklungsprozess für ein umfangreiches ESP-Programm in

Japan beschrieben, und die getroffenen Entscheidungen werden mit

Blick auf die Zielstellung und Zielerreichung diskutiert.

Stichwörter:

ESP, Curriculum-Design, fertigkeitsbasiertes Lernen, Komplexität

1 Introduction

The development of the field of

language teaching has availed teachers and course designers of a

large, sometimes seemingly infinite, number of choices as to how to

teach a course. In this paper, it is argued that English for Specific

Purposes (ESP) curriculum design should be approached systematically

to ensure that learners be given opportunities to develop skills and

knowledge relevant to their own contexts. Following such a systematic

design process enables pedagogical choices which are more appropriate

for learners.

Hutchinson & Waters (1987: 19)

define ESP as

an approach to language teaching in which all decisions as to content and method are based on the learner's reason for learning (Hutchinson & Waters 1987: 19)

Students

who are learning to be scientists and engineers require specific

language content, often called English

for Science and Technology (EST), which

is based on their need to operate effectively in their target

situation. This target situation has

quite specific language usage which is distinct from what students

learning for other pur- poses may

require. It is important to understand how language usage and skills

required differ in the various areas, and how we can teach these

skills more effectively. Curriculum design provides us with an

effective way to do so Nation & Macalister’s (2010) triadic

curriculum design framework will be described in the first part of

this paper. This description will include the factors which need to

be taken into account when designing an ESP curriculum and how

those factors contribute to the choices we are required to make. The

second part of the paper provides an example of designing a

curriculum for a large ESP program. It is hoped that through this

description of the curriculum design process, other curriculum

designers, be it for a large scale program such as this, or for a

single class course, will be enabled to approach what is a

complicated task in a systematic way, and go beyond their own

teaching experiences to make more effective choices.

2 Curriculum Design Framework

Nation

& Macalister’s (2010) triadic curriculum design framework

provides a convenient way to investigate the important factors

underlying

decisions required to formulate a

curriculum. There are three main aspects which require consideration.

The first one is the needs of the learners. The second aspect is the

situation in which the curriculum will be administered and the third

one is the selection of principles which will be central to the

creating of the curriculum. The essential factors identified in these

areas then combine to create a syllabus.

2.1 Learner

Needs

The needs of the learner are an

extremely important part of curriculum design as they essentially

determine what a learner needs to have achieved by the end of the

course. The ‘learner needs’ are made up of three parts (Figure

1):

Figure 1: The triadic

curriculum design framework

The

first part is an estimation of the skills and knowledge that the

participants will need in their target situation. This

part is usually determined by an

examination of the communication tasks that will be most commonly met

in the target environment. These can be expressed in terms of a

multitude of units, including a description of the structure of the

language used, the vocabulary, the speech acts, tasks, and pragmatic

content just to name a few. The second part is a description of the

learner’s current level. This is important as a starting point,

given both the limited amount of time, and the demotivating effects

of studying at a level which is too difficult or too easy. The third

part is an understanding of what the learners actually expect to

learn. If there is a major mismatch between the learner expectations

of the course and its content, then the program will lose face

validity, and as a result, the learners will not be motivated to work

towards the established goals of the course. The combination of the

target situation requirements and the learner’s current level helps

establish their needs.

2.2 The

Situation

Consideration

of the situation also influences the choices made in the creation of

the syllabus. There are three aspects of situation. The first one

represents

the constraints imposed by the learning environment. For example, the

resources available for learning are important in determining the

extent to which the goals of the program can be realistically met.

The characteristics of the classroom, the time available for the

learning to take place, and the budget available for the

administration of the program should all affect planning for

instance.

Learner

characteristics are also an extremely important aspect of situation.

These include the background of the learners, their learning styles,

and their collective experiences and beliefs. Their motivation and

the impact of the course on their lives, and the perceived importance

to them of the course they are taking, should also be considered

along with the number of learners participating in the program.

The

third aspect of the situation to be considered is the teacher. If the

ability of the teacher, and his or her knowledge and beliefs are not

fully taken into account, it is likely that the teachers in the

program will not

participate as completely as they could.

They will then be more likely to

teach according to their own beliefs as

to what is most appropriate for the

learners, even if this is different from the requirements of the

curriculum.

A final point is the degree to which

these factors can be changed to enable choices which are more

effective for meeting the goals of the curriculum. It is also

necessary to understand the resources, if any, which will be required

to make such changes. Some factors are resistant to change, or

require a large number of resources to prompt change. Buildings and

classroom layout are examples of this. Other factors are more

malleable or require relatively fewer resources.

The resources required to foster the

changes are highly context dependent. What is easy to change in one

context may be very difficult to change in another. The effect that

the individual factors have will also be different depending on the

educational context. Finally, altering factors which are easily

changeable may not actually have a positive influence on the choices

that can be made during the curriculum design process.

2.3 Language

Learning and Teaching Principles

The

third arm of the triadic framework for curriculum design is the

consideration of language learning and teaching principles. This is

where the results of the research from a number of fields are applied

to the choices we make in the curriculum. Interestingly, this is a

point of contention amongst both language teachers and researchers.

Many language teachers approach their teaching with the belief that

the generalization of research results to the language classroom has

little validity. Researchers also often

doubt the applicability of their or

others’ results. Robinson (1994), for example, suggested that a

language learning (or teaching) theory should be thoroughly tried and

tested before being applied to the language classroom. Ellis (1994)

responded by explaining that, while it is more desirable to have a

complete theory, in reality this development is not currently

realistic, and curriculum designers (and language teachers) need to

be able to make more effective educational choices for the classes

they teach.

Teachers left to their own resources

are only able to make choices based on their own experiences. When

teaching in a new situation, these may not necessarily provide the

choices which best match the new context. The application of the best

currently available principles to the design of the curriculum will

enable designers and teachers to go beyond their experience and make

more effective choices.

Principles

can be categorized into four types based on the area of syllabus

design they influence. They are content, sequencing, format and

presentation, and assessment principles.

Each of

these will be covered in turn.

2.3.1 Content Principles

Content

principles guide the selection of the issues which need to be covered

in the curriculum. The first and probably most important one links

‘needs’ to the content. It proposes that the content be relevant

to the target situation of the learners. They need to have the

linguistic knowledge and skills to enable them to perform effectively

in their target environment. Taking this need into account will

ensure that what learners are learning is useful to them, and

presupposes that, if learners understand that what they are learning

is relevant to their future needs, they will

probably be more motivated to learn.

The second principle focuses on

ordering the content in terms of its frequency of occurrence in the

target situation. This ensures that the time and effort spent on

learning items will be worthwhile in the target situation.

Vocabulary, for example, follows what is known as Zipf’s law of

distribution (Zipf 1949), where the most frequent items account for

the majority of the usage in the target situation. If the most

frequent 100 words account for roughly half of all running words -

and we might be lucky to meet a single occurrence of some lower

frequency words in one million running words - then time spent

learning the higher frequency words provides a much greater return

for effort.

Content should also cover instruction

in both communication strategies and language learning strategies. In

the majority of learning situations, instructional contact time is

always a major constraint. There will almost never be enough time for

students to learn all the necessary content. In order for students to

learn what is necessary to become effective in the target situation,

it is important to realize that much of the time they will spend

learning will not be in the language classroom. For this reason,

syllabi need to be designed to foster autonomy so that learners both

understand that they need to be responsible for their own learning

and have the tools to be autonomous learners.

Appropriate communication strategies

also need to be part of a well-designed curriculum. As mentioned

above, learners will rarely have the time to learn all the content

they will need to operate at an optimum level of performance in the

target situation. Communication strategies are taught so that when

learners find that they lack the appropriate knowledge, they will

have a strategy to make up the deficit.

In summary, a curriculum’s content

items need to be selected based on the needs of learners and then on

their frequency of use in the target situation. A good language

program would then also include strategies to assist with

communication and build autonomy in learning.

2.3.2 Sequencing and Ordering

Principles

After determining what content is to

be taught, the next decision is how to order it. If content can be

sequenced in such a way that it makes it easier for students to

learn, then that would make the learning process more efficient and

increase the amount of content that can be covered over the duration

of the course. Language learning theory has made various attempts to

determine what the best order of acquisition / learning is, but to

date no definitive answer has been provided, and this topic is still

the subject of extensive debate (e.g. Skehan 2001, Robinson 2001).

The following are some guiding principles for the ordering of the

content.

The

first guiding principle is that the syllabus needs to progressively

move forward in developing learners’ knowledge towards meeting

their goals. One way to do this is to order the items with gradually

increasing complexity (Skehan 2001). The idea that increasing

complexity is effective comes from research based on three theories

originating in cognitive psychology. The first theory explored the

automaticity of skills (Anderson 1982). The second one investigated

limited attentional capacity and the third one looked at the noticing

hypothesis (Schmidt 1990).

The

results of investigations into these theories suggest that learning

takes place through a

conscious noticing, which makes a

connection between the incoming noticed information and the long-term

memory, essentially creating new connections and memories. This

noticing process requires attentional resources. In Anderson’s

model of skill learning, the consciously controlled processes

gradually become automatic, requiring less conscious attention. This

is the process of automatization.

Two important

processes in language learning require attentional capacity.

Attentional mechanisms are located in working memory, and working

memory capacity is limited (Gathercole & Baddeley 1993). The

result is that the amount that can be noticed, or become automatic,

is limited. This processing limitation has implications for how the

content in a given course should be organized. Information should be

provided in such a way that learners need to process only the new

information (the learning focus of the task), and have all other

aspects of the task under their control. This can be done by

controlling for the complexity of

the task and, as the course progresses, gradually increasing the

complexity so that it approximates that of the target situation.

(Although see Robinson (2001) for a rebuttal to this idea.)

In addition to gradually increasing

the complexity of the learning tasks, based on Anderson’s (1982)

ACT theory, spaced repetition should also be incorporated to foster

successful learning. In order to automaticize new knowledge, it needs

to be processed repetitively, thus increasing the fluency of the

learning. In accordance with the principle generated from Anderson’s

theory, content should be repeated in a number of different contexts

throughout the syllabus.

Thus, in summary, and although there

is not a consensus from the field of cognitive psychology, its

complexity can be used to determine the ordering of the information

we require learners to acquire, and this information needs to be

repeated at spaced intervals.

2.3.3 Format and Presentation

Principles

The

curriculum designer will also need to make choices about exactly how

the content will be presented. This is the how

of curriculum design. Many teaching ‘methodologies’ are directed

at this aspect of curriculum design. The audio-lingual approach, the

communicative approach, and the task-based approach are all examples

of ways to format and present content1.

Nation & Macalister (2010) have again suggested several guiding

principles which will assist in the choices that need to be made

here.

The

first principle is that the content should be presented in such a way

that learners have the opportunity to focus on form as they learn the

content. Learners

should also be given the opportunity

to have both meaning-focused input and output, requiring them to

understand and process the content in a manner meaningful to them.

Finally, there needs to be the opportunity to focus on the

development of fluent (automatic) usage of the items.

The second guiding principle is that

the content should be introduced in such a way that learners are

focused on the target content as much as possible. Deep, meaningful

processing needs to be fostered to increase the chances that the

target content will be learned and to make the establishment of

form-meaning connections easier.

2.3.4 Assessment Principles

The

final aspect of curriculum design is assessment, which may be

formative or summative.

This process determines if learners have actually met their learning

goals and is often referred to as achievement

testing.

A

basic principle in assessment is that any test must be a valid and

reliable assessment of what it purports to be measuring. A valid

assessment is a good measure of what it claims to measure. If

validity is not at an acceptable level, among other things, a given

test will have two main problems. This first one is that it will not

provide important information regarding the learner’s attainment of

the goals of the course. The second one is that learners will

perceive the tests to be unfair and thus lose confidence in the

program.

A

second principle is that assessment procedures need to be designed

and timed in such a way that they ensure feedback to learners. As

noted above, there are many purposes for a test.

However, for educational purposes, it should provide feedback

to learners informing them whether or not they have attained the goal

which was being tested for, and, if not, what else they might need to

do in order to develop their knowledge or skills to attain that goal.

In addition, the feedback must be provided in a timely manner

so as to ensure that learners have time to make the

appropriate adjustments in their performance and make further

progress towards the goals of the curriculum.

In summary, it

can be stated that principles need to be applied to the

learning program in order to determine what content will be taught,

the order that the content will be taught in, how the content will be

presented and taught to the learner, and how the attainment of the

goals will be tested. The principles chosen here have been largely

adapted from Nation & Macalister (2010). It is

important to point out that there are a multitude of other principles

available for selection, many of which may contradict those that are

listed here as they are based on competing learning theories.

2.3.5 The Syllabus

The syllabus is the practical side of

the curriculum. Each aspect of the syllabus should reflect the

principles of curriculum design: the content and sequencing, the

format and presentation, and monitoring and assessment. Once the

goals have been determined, materials to convey the content must then

be designed.

The

goals are statements of course objectives, a description of the

skills and knowledge that learners are expected to attain by

participating fully in the program.

The goals are

determined by first looking at what students need and then limiting

it to the most useful content through application of the relevant

principles. Then analysis of the situation suggests what is actually

possible given the available resources. At the end of the process,

the goals will be a list of language items, attitudes and skills to

be acquired.

The sequencing principles are then

applied to this list to determine (1) the order of instruction, and

(2) which items will actually be taught. Following this, they should

be reformulated and grouped into courses and lessons. The format and

presentation of the content is determined by the selection and

application of the appropriate teaching methodology and principles.

Finally, a valid and reliable testing program should be set up which

considers both the situation and the opportunity to provide feedback

to learners.

3 Application of the Framework

This

part of the paper briefly summarizes the ESP curriculum design

process for tertiary science and engineering students at a large

private university in Japan. Following the curriculum design theory

described above, first, the needs of the students will be analyzed

and then, the situation will be described.

3.1 Students’

Needs

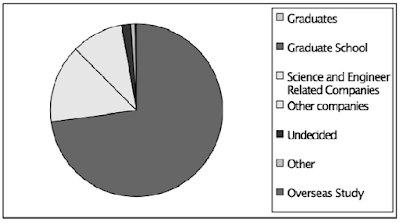

The needs of learners depend very much

on their target situation. According to the results of the exit

survey, shown in Figure 2 below, in 2012, roughly 90% of the students

continued in the field of science and engineering, with the majority

continuing on to graduate school. Thus, any ESP program needed to

develop English skills required in science and engineering. In

particular, many of the students needed to be able to conduct

research in science and engineering.

The

Faculty consists of seventeen different departments from a broad

range of science and engineering

disciplines, some empirical in nature and some rational.

The English required to conduct research in each of these target

fields is varied. However, there are commonalities across all of

them. These

include the ability to read, comprehend, and critically evaluate

research papers, the ability to conduct research in a group, the

ability to participate in international conferences, including giving

oral and poster presentations, and, finally, the ability to write

both proceedings and full research papers.

Figure 2: Where students

go after graduating

The

entry level of the students’ English language is another

consideration. The majority has

come through the Japanese education system, and has

learned English for at least six years, and perhaps longer. Japanese

schools spend a large amount of time working on reading and

translation skills. The best students are very proficient readers

through translation and also have a vocabulary of about 3,000 words

and a good knowledge of fairly complicated grammar. In contrast to

this, as the Japanese education system seldom focuses on productive

skills, these students cannot speak or write very well. It is

important to note, that, while the majority of students are products

of the Japanese education system, there are a small number of foreign

students and returnees who have studied in a foreign secondary

system.

Another major constraint arising from

the current knowledge of students is that their mastery of English to

date is extremely variable. Their TOEIC-IP scores vary from 10 to 990

(the average being 460). This is the full range. In addition, methods

of entry differ. Students are selected for entry to the university

and the Faculty of Science and Engineering through an entrance

examination which includes an English component. This examination

allows some control over the entry level of English. However, only

just over half of the students are admitted through the entrance

examination, and the rest are admitted by high-school recommendation

and through studying in schools affiliated to the university.

Many

of the students on the course have little understanding of their

English needs as researchers. They respond to questions about

personal goals for English with a variety of wants regarding their

future use of

English, which are

often related to

using English during overseas travel

and making friends with non-Japanese speakers. Many students also

respond that they have no particular need for English and that their

original purpose for learning English was mostly to meet university

entry requirements.

The

results of the needs analysis demonstrated that most of these

students will have a very clear necessity to operate as science and

engineering researchers in the international community and need good

English skills to achieve this. In addition, while the students

entering the university are fairly homogeneous in what they have

studied, the degree to which they have mastered the material is

widely varied. Finally, many of the students on the program have a

personal preference for learning English to make friends and travel.

3.2 The

Situation

The situation will be described in

terms of the available resources, the teachers on the program and the

learners. The first major resourcing problem is the contact time

available. Students are required to study English for two 90 minute

sessions per week for the first two years of their studies. Courses

are available in their final two years of undergraduate studies, but

they are optional.

Funding

for teachers is

also limited. This influences the number of students in classes which

average 35 students. Such large groups place major limitations on the

kinds of interaction that can take place in the classroom and the

types of assessments that can be conducted. Although teacher funds

are limited, there is access to a computer-based content delivery

system and a learner management system. The classrooms have access to

wireless Internet, DVD / CD / Blue-ray players, projectors, and

blackboards. Computers can be borrowed for classes. Photocopying

facilities are available for all teachers, and, in principle, there

is no restriction on the number of copies made. Finally, students are

charged a yearly fee that provides a budget for running the program,

and are expected to pay for textbooks.

Apart

from a small number of permanent staff, who may also teach in other

areas, the resources available only allow for hiring part-time

teachers. All have at least

a Master’s degree in language teaching or equivalent, and at least

two years of teaching experience at

tertiary institutions. In addition, an understanding of a principled

approach to language teaching and an understanding of what is

required to teach in a coordinated curriculum are necessary. Finally,

preference is given to teachers who are able to spend at least 90

minutes of preparation and grading per 90 minutes of contact time.

As

previously mentioned, many of the learners are high school graduates

who believe that they have little need for English. However, they are

very effective learners. As they have chosen their fields of study

and, thus, are interested in science and engineering, they are more

motivated to learn content related to these fields. The intake is

very large, with 1,700 to 1,800 students being accepted every year.

The implication of this is that there is great variety among

students, and a large number of personality differences. 90% to 95%

of the students are male. There are also a small number of students

with learning disabilities and social disorders. In addition,

between 5% and 10% of the students fail the courses, and are required

to retake them in order to graduate.

3.3 The

Syllabus Overview

The

syllabus was created as a result of choices that have been made

due

to the situation described above. The

needs have been organized into a set of

goals which were

ordered based on the principles. In the following section, the

syllabus will be described.

The

brief summary of the program demonstrates that it has taken into

account the analysis of the situation. First-year students take four

compulsory courses: two in their first semester and two in their

second semester. They are Communication

Strategies 1 and 2 and Academic

Listening Comprehension 1 and 2. The

course Communication Strategies

focuses on developing speaking and

discussion skills, and the course Academic

Lecture Comprehension focuses

on developing critical listening skills. Second-year students are

expected to take an additional four compulsory courses. Concept

Building and Discussion 1 and 2 is a

task-based course which requires students to design simple research

projects, collect the data, and report the results

of their studies both orally and in a research paper. In the course

Academic

Reading 1 and 2,

students

develop reading strategies and reading fluency. In their third and

fourth years of study, students are able to take elective courses

called Technical Presentation

and Technical Writing.

As their names suggest, these courses focus on developing research

presentation skills and technical writing skills. Similar courses are

also available at graduate school level for students who did not take

these courses at undergraduate level.

3.3.1 The Syllabus Goals

The

above

needs analysis demonstrated that most of these students will need the

ability to participate in international research groups. In order to

do this, they must be able to discuss, and explain their ideas, ask

and answer questions, and support their own opinions. As they have

little experience of speaking or of critical thinking, these two

goals were included in the syllabus with the aim of enabling full

participation in research-based discussion. Students also need the

ability to present information to a larger audience. In order to do

this, they must be able to create visual aids, give a comprehensible

talk to an international audience and be able to answer questions.

Thus, a presentation goal was added which has these three components.

A third skill required is the reading of technical papers, and the

critical evaluation of these papers. A reading goal aims to increase

the reading fluency of the students, and encourage the development of

other comprehension strategies than just translation. Writing

proceedings and full papers is another required skill. In order to

develop this facility, a writing goal was established. The final goal

was to improve

skills allowing students to participate fully in international

conferences. In practice, students must be able to listen critically

to oral and poster presentations. This requires a listening goal, a

critical thinking goal, and a goal aiming at the ability to ask

questions after a presentation. A second part aims at developing the

ability to interact with other researchers during conversation. The

discussion goal was adapted to include this skill as well. In total,

a list of six goals was developed. These included ‘to develop the

ability to use English to confidently take part in: scientific

discussion, technical presentation, technical writing, technical

reading, listening, and critical thinking’ (see

Figure 4). In addition, it was determined

that, while most students had a large vocabulary based on translating

the meaning of English words into Japanese, they were not really able

to use a lot of these words in communication. For that reason, a

vocabulary usage goal was also added.2

3.3.2 Content and Sequencing

Swale’s

(1990) move’s analysis suggests that texts with similar

communicative functions have common

‘moves’.

His ideas can be applied to communication of a high volume of

information when much of the information is organized in similar

ways. For example, a paragraph describing a process typically begins

with a topic sentence describing or introducing the process. Then

each subsequent sentence provides a step in the process with

predictable transitions between each of the moves (steps). The

syllabus content was built around models of common “structures”,

which occur in the presentations students give or listen to, the

discussions, and the papers they should be able to read and write.

These structures were abstracted from activities like describing a

process, supporting an opinion, solving a problem, and describing

data, to name a few.

The content was

then sequenced based on the two principles described above,

complexity and repetition. Thus,

the basic language structures were repeated several times throughout

the syllabus as the communicative tasks which required their use

increased in complexity, gradually approximating the tasks that need

to be performed in the target situation. Figure 3 below provides an

example of this, aimed at meeting writing goals. The process

structure was covered at multiple times

throughout the syllabus. It was first provided in the first year as a

task requiring a summary paragraph of a process lecture (in Academic

Lecture Comprehension).

The second repetition in this spiral format required students to

complete a spoken task following the process

structure and then write out the task

(in Concept Building

and Discussion 1).

A third repetition required students to do a research project,

including description of their research method as a process during

the class, in a progress report and in written research papers

(Concept Building and Discussion 2).

Finally, in Technical Writing 1 and 2,

students are required to describe their own research methods in a

format approximating that of their research field.

Figure 3: The development

of the process structure

Figure

4 provides a brief summary of how each of these goals is developed

through the program. The speaking / discussion goal is developed

first by beginning with spoken fluency tasks. These are designed to

get students to use the large amounts of knowledge they have built up

through their high-school years in actual communication. The next

step is to provide more structured tasks,

whose learning goal is the acquisition

of the structures discussed above. Here, students start to learn how

to express their opinion, for example. Following this, in their

second year, students are expected to develop group research projects

beginning with group discussion.

Presentation

skills are developed first by establishing

the students’ ability to ask and

answer questions. This is done by explaining common questioning

structures and also by looking at types of questions

to be asked. Advanced students begin by

presenting their opinions in their first year. In their second year,

students present their research,

first in groups, and then individually. Students are also required to

ask questions which the presenters answer. Finally, students present

their research accurately, following the genres common to their field

of study.

One

goal shown in Figure 4 is a writing one. The skills to achieve this

are built up initially by asking students to write single paragraph

summaries following a particular structure. In the second half of the

first year, this task becomes more complex, requiring multi-paragraph

summaries. In the second year, the focus moves from producing

summaries to reporting of students’ research, which combines

structures to result in a full Introduction-Method-Results-Discussion

paper. Finally in their third year, students produce a full

proceedings-style paper which approximates the papers written in

their fields of study:

Figure 4: The syllabus

goals sequenced

The

development of reading skills begins with the reading of single pages

on the same (science-based) subjects that have been listened to

in oral presentations. This process

aims to build up reading fluency. In the second year, reading

strategies are taught to provide students with more strategy choices

for text comprehension than the grammar-translation strategy most

have been taught in high school. In addition, students are taught

critical Internet search skills, and how to read an academic paper.

Technical reading is also integrated into the third-year advanced

courses.

Listening

begins with lectures and talks which are created around the model

structures.

In their

first year, each talk is built around one structure. In their

second year, students have the opportunity to listen to, and

evaluate, presentations produced by their peers. In addition to

listening, the ability to ask questions is also taught. This starts

by explaining the discourse structures and the moves required when

asking a question. Students are also taught the different types of

questions they can ask, and some sample phrases they can use to

scaffold their questions. Students

are also

required to ask questions during

presentation.

The

vocabulary learning part of the program is the most obvious

application of the frequency principle. In

their first year, students are expected to further develop their

knowledge of the most frequent 2,000

words. In their second year, the

focus is on the academic word list. Beyond this, the aim is that

students will build a general technical vocabulary and then the

technical vocabulary which is specific to their field of studies. The

vocabulary that is covered in the program is nowhere near what a

native speaker would have access to, but it is hoped that it will be

enough to begin to communicate effectively in the target situation

and allow further development in future years.

The

final goal described here is critical thinking. This goal is

developed on several fronts. The first is in expressing opinions.

Here, learners are first taught that,

when expressing an opinion,

they are required

to support it with a reason. This is further built upon by explaining

that reasons need to be evidence based. Following this,

students are taught how to evaluate the quality of evidence. Finally,

they need to integrate whatever knowledge they have acquired into an

academic discussion where they argue and support their own

interpretation of research results. A second area aimed at developing

critical thinking involves asking questions. Here, students are

taught to ask questions by focusing on the quality of evidence. They

are also taught how to express their own opinions through the use of

questions. A final area aimed at establishing critical thinking is

the development of students’ ability to evaluate published

research. This last area of the syllabus is still in development.

3.3.3

Format and Presentation

The

syllabus is supported by a combination of in-house and commercial

textbooks in conjunction with supplementary materials. The textbooks

are Communication Strategies 1 (2013) and Communication

Strategies 2 (2013), Academic Listening Comprehension

(2006) for the first year; Concept Building and Discussion:

Foundations (2009), Concept Building and Discussion:

Applications (2009) and Reading Skills for Academic Success

(2004) for the second year; and Writing Up Research in Science and

Engineering: Foundations (2011), Writing Up Research in

Science and Engineering: Developments (2012) and Presenting

Research in Science and Engineering (2009) for the advanced

courses.

The

organization of the in-house Communication Strategies

textbooks follow the four-strands principle described above, which

states that a course should equally cover focus on form,

meaning-focused input, form-focused output, and meaning-focused

output. A typical unit begins with meaning-focused input which

contains the target structures. Here, students need to process the

meaning of the input to complete a communicative task. The next step

is the provision of a section focusing on form. The form of the

target structure is explained here, with examples. In addition to the

introduction of the structure, some communication strategies are also

taught, which provide assistance in actually applying the structures

in practical communication tasks. Once the structures are taught,

students are able to check if they have understood them by listening

to examples of meaning-focused input again, this time focusing on the

form. Form-focused output is next. Students are required to create

self-contextualized role plays which allow them to integrate the

learned structure into controlled output. The final section presents

meaning-focused output. Communication tasks are provided, which can

be effectively completed by use of the structures taught in the unit.

Examples of the structures in use are also provided.

3.3.4

Assessment

The

last part of the syllabus is the assessment of the goals. Here, a

criterion-referenced approach was adapted. A criterion, or set of

criteria, was selected for each goal, and students were required to

demonstrate that they were capable of meeting

this minimum requirement before they were able to pass the

course. The criterion reference was used to ensure that students had

attained a minimum standard required to pass the course. In addition

to determining if the students had attained the criterion, each

assessment was graded based on the degree to which the goal had been

attained. This score determined their course grade.

As

the criteria are referenced to the skills that will actually need to

be demonstrated in the target situation, it is assumed that assessing

the extent to which they are met is providing valid and reliable

assessment. However, as there is a large number of teachers using

these assessments, it is difficult to determine their validity and

reliability without doing an empirical study. This is planned for the

future.

Each

criterion was measured several times during the course, and it is

hoped that teachers have provided timely feedback to students. In

this way, students would be able to see which of the criteria they

were not meeting and which overall goals they were not achieving well

on and how they could alter their performance during the next test or

task to demonstrate that they had attained the knowledge or skill

required for the course. Again, whether this is actually happening

course-wide is a subject for further research.

4 Conclusion

The

triadic ESP curriculum design process (Nation & Macalister 2010),

consists of first conducting a needs analysis and a situation

analysis. This is followed by selecting language learning and

teaching principles which are most relevant for the situation. Once

this is done, the language learning content is determined by

separating the needs into teachable units and sequencing them based

on learning principles. The resulting list

becomes a list of program goals.

Following this, the format and presentation of the syllabus

are determined, which results in textbooks and materials designed to

assist the learner to attain the goals effectively. Finally, an

assessment program is designed to both test

the student’s attainments of the goals, and to provide useful

feedback to assist in the final attainment.

This

paper has provided a brief summary of the curriculum design process.

It is hoped that by providing this example, both language teachers

and curriculum designers will be able to not only better understand

the links between language learning and teaching theory, and the

language classroom, but also be able to create better links between

theory and practice, which, in turn, will make their teaching more

effective.

References

Anderson, J. R.

(1982). Acquisition of Cognitive Skill. In: Psychological Review,

89.4 (1982), 369-406. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.89.4.369

Anthony, L.

(2009). Presenting Research in Science and Engineering. DTP

Publishing: Tokyo.

Anthony, L.

(2011). Writing Up Research in Science and Engineering:

Foundations. Waseda University: Tokyo.

Anthony, L.

(2012). Writing Up Research in Science and Engineering:

Developments. Waseda University: Tokyo.

Anthony, L.,

Rose, R. & C. Sheppard (2010). Concept Building and

Discussion: Foundations. 2nd Ed. DTP Publishing:

Tokyo.

Ellis, R.

(1994). Implicit / Explicit Knowledge and Language Pedagogy. In:

TESOL Quarterly, 28.1 (1994), 166-172.

Gathercole, S.

E. & A. D. Baddeley (1993). Working Memory and Language.

Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hove.

Hutchison, T. &

A. Waters (1987). English for Specific Purposes: A

Learning-Centered Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

Nation, P. &

, J. Macalister (2010). Language Curriculum Design. Routledge:

New York, NY.

Robinson, P.

(1994). Comments on Rod Ellis’s “The Structural Syllabus and

Second Language Acquisition”: Implicit Knowledge, Second Language

Learning and Syllabus Construction. In: TESOL Quarterly, 28.1

(1994), 161-166.

Robinson, P.

(2001). Task Complexity, Cognitive Resources, and Syllabus Design: A

Triadic Framework for Examining Task Influences on SLA. In: P.

Robinson (Ed.) (2001). Cognition and Second Language Instruction.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rose, R. &

L. Anthony (2010). Concept Building and Discussion: Applications.

2nd Ed. DTP Publishing: Tokyo.

Schmidt, R.

(1990). The Role of Consciousness in Second Language Learning. In:

Applied Linguistics,

11.2 (1990): 129-158.doi: 10.1093/applin/11.2.129.

Sheppard, C.,

Fujii, M., Manalo, M., Tanaka-Ellis, N. & Y. Ueno (2013).

Communication Strategies 1. DTP Publishing: Tokyo.

Sheppard,

C., Fujii, M., Manalo, M., Tanaka-Ellis, N. & Y. Ueno (2013).

Communication Strategies 2. DTP Publishing: Tokyo.

Skehan, P. &

P. Foster (2001). Cognition in Tasks. In: P. Robinson (Ed.) (2001).

Cognition and Second Language Instruction. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Swales, J. M.

(1990). Genre Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Upton, T. A.

(2004). Reading Skills for Academic Success. The University of

Michigan Press: Ann Arbor.

Zipf

GK (1949). Human

Behavior and the Principle of Least Effort.

Cambridge, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley.

____________

1 These approaches also inform other aspects of curriculum design,

sequencing and assessment in particular.

2 There

is also a plan to develop students’ autonomy. However, this will

be added when further resources are available.